You can support this blog by becoming a patron on Patreon: Fund me, baby!

|

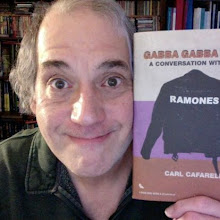

| Finish the damned story, Carl! |

PART ONE: 1967-1971

Unfinished And Abandoned digs deeeeep into my unpublished archives, and exhumes projects that I started (sometimes barely started) but abandoned, unfinished. I am such a quitter.

My creation Jack Mystery and I go back a looooong way. When I was a kid in the mid '60s, I liked to play out superhero scenarios with whatever was at hand. My tools for these fanciful adventures included my Captain Action doll and accessories; I don't think I'd yet heard the phrase "action figure," but our Cap was a doll of steel who could transform himself into Superman, Batman, Captain America, The Phantom, Aquaman, Flash Gordon, Steve Canyon, The Lone Ranger, and Sgt. Fury, and I owned all of those costumes-sold-separately. I would also incorporate my sister's leftover Barbie dolls, my Creepy Crawlers, stuffed animals, various knickknacks and tchotchkes, my own drawings, and probably my lunch leftovers to concoct intricate, fanciful exploits for superheroes and super-villains, both existing characters and theoretically original creations. The "original" creations were highly derivative, and included names like...um, Batman (later re-named The Bat, really a Hawkman ripoff with batwings) and The Avengers. My crimson-colored Superman Creepy Crawler became The Scarlet Red Man. A painting I did in elementary school, depicting a bubbling, amorphous alien creature, became a superhero called Gloppy. I suspect that Stan Lee never wasted much time worrying about competition from seven-year-old me.

Among the random items at hand was a set of little James Bond-related statues. The only one of these I remember was a figure--Largo--dressed in a light-colored suit, sporting an eye-patch and a gun. I made him a superhero, and I named him Mr. Mystery.

My superhero play expanded from action figures into home-made comics. Usually not complete stories (though there were one or two of those), but cover concepts, heavily influenced by Marvel Comics. I envisioned my own comics line, Imperial-Universal Comics, and I scribbled ideas in long-since-discarded notebooks. My flagship title was a showcase book called Universal Suspense (inspired by the Marvel Super-Heroes comic book), depicting my heroes Gem, The Power, Rain-Hat Sam (don't ask), and other mighty forgettables clashing with nogoodniks like The Bolshevik Bat and The Vortex.

And, of course, there was Mr. Mystery.

Initially, Mr. Mystery was, I think, a non-powered hero who flew with the aid of some artificial means, and used what I called an Evri-Gun, capable of firing bullets, laser beams, or whatever other projectile or energy pulse the situation demanded. From there, I decided I wanted to change Mr. Mystery's appearance, ditching the suit and eye-patch in favor of a more traditional superhero costume. A weird explosion somehow caused Mystery's lost eye to regenerate itself, eliminating the need for the patch. He donned a skintight light blue costume, with black boots, black belt and holster, and golden jet pack, And he decided to go by his full name, rather than the needlessly formal Mr. Mystery. Henceforth, he would be Jack. Jack Mystery.

From these childish origins, Jack Mystery nonetheless became the one original character I came back to the most often over a span of a few decades. In the '80s, I started tweaking the concept into something that almost might have worked, but I never completed the work. The only Jack Mystery project I ever saw through, start to finish, was a proposed Jack Mystery newspaper strip that I penciled for Mr. DiGesare's art class in eighth grade, 1972-'73. That's where we'll pick up the story when Unfinished And Abandoned: Jack Mystery returns.

PART TWO: 1972-73

|

| Jack Mystery in the '80s |

Eighth grade was the closest I came to fitting in since leaving elementary school. I still didn't actually fit in, mind you--I was as square a peg as I'd always been--but camaraderie, normalcy, seemed almost within reach, more so than at any time since fourth grade. For the rest of my life, I would never come that close again.

1972 to '73, eighth grade, was my final year at Roxboro Road Middle School. I hated that place, though not as much as I would come to hate high school after that. Nonetheless, that year offered glimpses of bliss, sporadic moments of contentment. My quirks were acknowledged and, if not quite embraced, at least tolerated. I had a few friends. I started a comic book club at school. I wrote. My love of Charlie Chaplin and The Marx Brothers was met with an indifferent shrug, which was better than being met with rolled eyes and insults. It was as near to a happy time as anything else I can remember from secondary school.

One of the happiest memories was art class with a teacher named John DiGesare. Mr. D was the teacher everyone liked, a gentle and enthusiastic soul who encouraged all of us to create. He would play records in class--usually Carole King's Tapestry or James Taylor's Sweet Baby James--to provide atmosphere and inspiration. While I might have preferred to listen to The Beatles or Badfinger or Alice Cooper, the music on Mr. D's turntable served the essential purpose of nurturing our nascent adolescent artistry. One week, as Sweet Baby James played, Mr. D charged us with the task of making something based on the music we heard. I used the mourning of "Fire And Rain" and the ersatz blues of "Steamroller" to conjure a comic strip called The Adventures Of James Taylor, depicting our intrepid title character mourning the death of a close friend while contending with an imposing spectral figure in the cemetery: Death personified, crying out a defiant introduction, I am THE BLUES!!

Chilling.

Okay, it was neither Proust nor Spillane, not Will Eisner, not even the cartoon equivalent of Ed Wood. But it was mine, created in an environment that encouraged the pursuit and exploration of ideas: pure, fanciful ideas.

I have several specific memories of Mr. D's class. One Spring day, I brought in a couple of comic books--Batman # 250 and Shazam! # 4--to show the teacher, and any other interested parties. I recall my classmate Marge Dugan--whom I always thought was kinda cute--thumbing through the Batman comic, and not seeming openly dismissive of the idea of superhero comics. Cute girls digging superheroes? Well...cool! And Mr. D and I discussed his childhood favorite, the original Captain Marvel. I told him that DC Comics had recently acquired the character from former rival publisher Fawcett, after successfully suing Cap out of existence in the '50s. Mr. D dismissed DC's claim that Captain Marvel had been a copy of Superman (and therefore a violation of the Man Of Steel's copyright) with a disdainful one-word response: Rubbish!

My love of The Marx Brothers prompted me to make a paper mache Groucho, which lacked the accomplishment of my friend Richard Dean's W.C. Fields, but which I kept for years thereafter until it was decimated by time (and, possibly, Erin Fleming). My only negative memory of art class with Mr. DiGesare was the time Richard Dean, Jeff Greco, and I got carried away with horseplay and began throwing clay around the room. Our obnoxious antics were finally enough to try even Mr, D's seemingly infinite patience, and he yelled and sent us to the Dean's office. The Dean, Mr. Mandarino, was visibly shocked that anyone could have ever misbehaved badly enough to make John DiGesare lose his cool. Mr. Mandarino contained his surprise just enough to ask us, What did you do...?!

(Many years later, I recounted this story of my trip to the Dean's office to Mr. DiGesare, and he was mortified. He started to apologize, but I immediately told him, No, we deserved it!)

But my favorite among favorite memories of Mr. DiGesare's art class was Jack Mystery. I had never really let go of this superhero I'd created as a child. Given an opportunity to work on any long-form art project of our choosing, it was inevitable that I would want to work on some comics. Inspired by the vintage strips I'd recently been reading in a hardcover collection called The Collected Works Of Buck Rogers In The 25th Century, I settled on the idea of doing Jack Mystery as a newspaper comic strip serial.

Man, I worked on this, diligently, every day. Okay, as diligently as you'd expect from a lazy and distractible 13-year-old, but I did work on it. By making it a daily strip, I was able to work in black and white, and not be concerned with adding the color I knew I'd just mess up anyway. I worked in pencil, on cheap-cheap paper, reflecting the superhero's pulpy roots. Mr. D often tried to cajole me into working with ink, but I insisted on pencils only. I felt greater control with pencils, and Mr. D acquiesced.

I still have those Jack Mystery strips. Somewhere. Somewhere here, in this vast accumulation of stuff. I haven't seen them in years, but I remember the vague story of police officer Jack Mystery, wounded while thwarting a robbery, somehow gaining super strength and resilience in the process. Mystery quits the police force to become a superhero, aided by his brother Carl, who develops a jet pack that enables Jack to fly. Jack and Carl investigate the crime ring terrorizing the city, and eventually discover its mastermind to be Jack's former boss, the chief of police. Seeking to escape justice, the crooked police chief murders Carl Mystery, but is unable to elude the wrath of the grief-stricken Jack Mystery. The serial ended with a single color Sunday page, as Jack Mystery captured his brother's killer, and vowed to remain vigilant in protecting the innocent and thwarting the corrupt. Carl Mystery's sacrifice would not be in vain.

I wrote and drew at the same time, with no blueprint or master plan. If I were to read it today, I'm sure its amateurishness would make me cringe. But I would still take pride in the effort, in the sheer, fevered exuberance of the creative act, no matter how puerile the result, how feeble the execution. It was mine. It still is.

Mr. DiGesare encouraged me the whole way, spurring me on, suggesting I try working in ink, and having me talk to Mr. Yauchzy about doing Jack Mystery for the school newspaper. Mr. Yauchzy compared it to Dick Tracy, and said he wanted to find out what happens to the poor guy, but I never pursued that. I think Mr. D may have also mentioned that I oughtta do it in ink.

The single best day of this whole experience was when Mr. DiGesare took a bunch of his students away from the school, and had us set up in the lobby of a bank for an afternoon of work on our projects. I can't convey the meaning such a simple setting can have for someone who wants to pursue a creative endeavor. Here's a forum. Here's a platform. Here's a stage. Here's a soapbox. Perform. Create. Imagine. Do. Your work is worthwhile. Keep working on it. I labored contentedly on my Jack Mystery comic strip, writing and drawing before this passive audience of tellers and account holders, and I knew with absolute certainty that this was what I wanted to do with my life.

But I didn't do that.

Eighth grade ended, and I bid farewell to Mr. DiGesare and to Roxboro Road Middle School. When ninth grade commenced at North Syracuse Central High School the following September, I told my freshman art teacher that I really wanted to become a professional comic book writer and artist, and that I hoped he'd be able to help me hone my skills to achieve that dream.

He didn't like my attitude. Later on, at a parent-teacher conference, he told my mom and dad that he felt he needed to break me. My freshman year art class was a disaster. I took one more year of art after that, and then never took another art class again. I continued to sketch and doodle--I still do that constantly--but I didn't see a path to becoming an artist. So I gave it up.

Never underestimate the value of a good teacher. Never underestimate the danger of indifference either, nor the dangers of a closed mind and a rigid attitude. Could I have ever become an artist? I don't know. I had some ability; it was raw, and in desperate need of development, but it was there, in all its unformed uncertainty, waiting to be set free. Mr. DiGesare opened the door; his successor locked it and sealed it shut. My failure to overcome that is still on me, of course; if I'd been more persistent, and worked harder to improve my craft, I could have overcome the sudden lack of support and encouragement. Can't always blame others for my mistakes. Just sometimes.

For all that, though, I didn't quite surrender the notion of creating. I kept writing, for sure; no one would ever be able to take that away from me. But I kept drawing, too. I slowly got a little better, and I can only wonder how much better I could have become if I'd felt encouraged to continue with it.

I see Mr. DiGesare occasionally. He's a regular customer at the store where I work. When he sees me, he tells me to get off the computer and get back to drawing something. I reply that I'm writing, and that's just as good. But then I also show him the scraps of paper all around me, the quick sketches I've done recently (usually of Batman; no, you grow up). He smiles, and encourages me to keep at it. Never stop drawing. It's good advice, from a great teacher. And it's a good memory, from as good a year as I ever had back then.

My eighth grade Jack Mystery comic strip was the only complete story I ever did with this character I created so long ago. But, in the '80s, I had some ideas. I never got very far with them, but I was thinking of ways to do a Jack Mystery comic book, completely revamped, centering on the story of a dissipated young movie actor who finds himself cast in the role of a comic-book superhero, and finds himself literally becoming the super character he plays. We'll discuss those plans when Unfinished And Abandoned: Jack Mystery concludes.

PART THREE: The 1980s

I think I was 13 when I knew I wanted to become a writer. I could have been as young as 12, maybe as old as 14, but 13 seems most likely. It was a specific moment of revelation; I was at a wedding reception, doodling comics in my notebook, and another attendee asked me what I was doing. From there, the short conversation settled upon the idea of, well, was I thinking of writing comic books professionally? A magic light bulb illuminated my curls and dandruff. Yeah, I thought. Yeah, I could do that.

I started writing a Batman script right then and there. My path was decided. I was going to be a writer.

I've already spoken at length about the amateur comics I churned out as a kid in the '60s and early '70s, and my ambition to be both the next Stan Lee and the next Jack Kirby, all rolled into one. But this was different. Prior to this, I don't think it even occurred to me that I could pursue writing separately, that I didn't have to be the artist depicting the POWs and BAMs my imagination concocted. I'm not certain whether this took place before or after the eighth-grade Jack Mystery comic strip we talked about last time; I suspect it was after, perhaps fueled by the lack of encouragement I encountered in ninth grade art class. Fine. I wasn't forsaking my artwork, but I would focus on writing. It was time to put aside the foolish drawings of youth, and concentrate instead on the foolish word balloons and captions of youth.

Unencumbered by anything resembling humility or common sense, I started submitting stuff to DC Comics immediately. Hell, I submitted that first handwritten Batman story I'd thrown together at my cousin's wedding, an inept tale of The Dark Knight visiting Syracuse and investigating the death of a teenager apparently killed by police, a narrative scrawled with dubious legibility on spiral notebook paper. DC had superstar artist Neal Adams illustrate it, and together we won the Shazam Award for best comic book story ever. Playboy Playmate Deanna Baker read it, loved it, and asked me to move in with her. Success!

|

| We were made for each other, Carl! |

I kept bothering them nonetheless. A handwritten Shazam! story, with the original Captain Marvel facing off against a suddenly super-powered incarnation of his arch enemy Dr. Sivana, a story which may or may not have guest-starred Plastic Man. A typewritten Batman script called "The Overtime Crimefighter!," depicting 24 hours in the life of the Caped Crusader. And "Nightmare Resurrection," a ten-years-after sequel to the classic 1966 Batman story "Death Knocks Three Times." The latter was accompanied by art samples drawn by my friend Mike DeAngelo, a talented artist with whom I hoped to partner; this submission did at least merit a form letter rejection from DC. But I kept on writing. I didn't succeed at any of it, but I kept on writing.

Jump ahead now to the mid '80s. I was still writing, still doodling, still attempting to craft...something. Record reviews. Short stories. A history of The Ramones. More submissions to DC Comics, including original characters (wait, let's make that "original" characters, with the quotes) Captain Infinity,The Trident, and Lawman, plus existing properties Batman and The Justice League of America. I finally sold something, a history of the comic book Secret Six, published in Amazing Heroes in 1984. It was the start of my spotty freelance career (the beginning of which I've chronicled in some detail as The Road To Goldmine). My sales were all nonfiction, but I kept trying my hand at fiction, too.

I'm not sure of the precise chronology, but I did return to Jack Mystery in this time frame. I'm gonna say it was 1985, because ol' Jack is certainly a presence in the sketchbook I was using that year. I did sketches of Jack, jotted down fragments of story ideas, and began to map in my head a whole new approach and narrative for this hackneyed hero I'd created in elementary school. I never quite got around to actually writing it. And that's a shame, because of all of my half-baked and raw attempts at comic-book creation in the '80s, Jack Mystery was the only one that had potential, the sole possibility of something that coulda been, y'know...cooked, maybe even well done.

The new concept of Jack Mystery in the '80s was heavily influenced by the independent comics I was reading, particularly things like American Flagg, Nexus, Zot!, Mark Evanier and Dan Spiegle's Crossfire, and even Love And Rockets. It was also influenced by the idea that the comics industry had mistreated and abandoned many of the creators who'd built it; Jack Kirby was in the news for his efforts to get Marvel to return his original art, and I remembered well the plight of Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, and of then-uncredited Batman co-creator Bill Finger (who died in poverty), all cast aside by a comics business that would never have existed without their efforts. My notes are incomplete, but this is cobbled together and built upon what I remember of my '80s reboot of Jack Mystery:

--

Let's face it: actor Trevor Harris is kind of a schmuck.

Maybe he doesn't mean to be such a jerk, but he is one anyway. He's faithless and seemingly amoral, with two ex-wives and a long (and lengthening) list of broken relationships, all before the age of twenty-six. He drinks too much. He parties too long. His one successful role, as young Dr. Champion on the soap opera Temptations, disappeared when producers, fed up with his erratic behavior, had the writers put poor, poor Dr. Champion in a near-fatal car accident, prompting facial reconstruction surgery that allowed the role to be recast with a less difficult team player. The fresh face of Harris' replacement is on all the magazine covers; Harris hasn't worked since.

But there are still people who love him. He has fans, and he has family back in Buffalo. In Buffalo, he was just Joey Lichtenberg, and his parents owned a restaurant; his older brother Charles took over the restaurant when their parents died, remaking it into a small, successful local chain of chicken wing places, Wings Over Buffalo, with a plan to go national as Wings Over America. Charles begs Trevor--Joey--to come home and join the family business. Joey's first wife, Trish, still lives in Buffalo, too. They no longer speak. Joey--Trevor--is adamant that he will remain in Hollywood. And he drinks some more.

Our narrative opens with Trevor alone in his apartment, face-down in bed, sheets and covers askew, slumbering in the last seconds before the morning hangover kicks in. There was someone with him in bed last night--Marcie? Darcey? Canarsie? Veronica? Betty? Sabrina? Ethel? Something like that?--but the sweet young thing had extricated her curvy derriere and split before the sun's rise, sensing that she didn't really want to be there when the jerk awakened. Carrie! That was it. Trevor would prefer to remain in bed for a few more decades, dreaming of simultaneous carnal bliss with Madonna and Joan Jett, but the insistent, relentless ringing of the phone finally nags him into the real world.

Did you forget your goddamned audition today?! Trevor's manager, Morrie. I hadda practically sell a frickin' lung to get you a shot at this, and you're gonna blow it by not even showin' up? GET YOUR ASS DOWN THERE, YOU ASSHOLE!!

Grumbling, Trevor stumbles out of the bedroom, cursing loudly. He doesn't bother shaving, or showering, or even changing his clothes; he's still wearing the Ramones T-shirt and black jeans he had on when he picked up Carrie (no--it was Marcie! Or Cheryl. No, Marcie!) in the million years ago that was last night. He swishes mouthwash, swallows five aspirin, pulls on Beatle boots, and climbs into the '69 Impala his Dad gave him. He somehow makes it to the studio in time.

It's open casting, he thinks to himself. It's not like Morrie got me some inside line on a surefire role. And it's based on a friggin' old comic book, for God's sake. I need a new agent.

"A friggin' old comic book?" Oh, Trevor--if you only had the merest idea about how much your life is about to change.

Jack Mystery Comics debuted in 1942, a quarterly book published by a fly-by-night outfit that was able to get ahold of paper even during wartime rationing, and needed to keep its presses running. The title feature was created by the team of Kirby Simon and William Hand, and the book was concocted hastily by their studio. Never a big success, the book hung on into the early '50s nonetheless. Jack Mystery was a rather generic superhero, dressed in red, white and blue (with black belt and holster), possessing super strength and resilience, and able to fly with the aid of a rocket jet backpack. Jack fought the usual comic-book assortment of gangsters, Axis agents, fifth columnists, and the occasional super-villain, like his arch-enemy, Dr. Skeleton. A planned Columbia movie serial was abandoned. A 1952 TV pilot went unsold. Jack Mystery vanished from the stands.

The character was subsequently acquired by the company that would eventually become the giant Imperial Communications conglomerate. The success of the Batman TV series prompted a new Jack Mystery comic book series in 1967, and even a cult-classic high-camp feature film starring Lyle Waggoner. Jack Mystery's popularity exploded in the early '80s, thanks to a deconstruction and revamp by the superstar writer/artist Miles Franklin, a hipper-than-hip comic book championed by Rolling Stone and now about to be adapted into a major motion picture. The film's producers just need to find the perfect actor to be the new Jack Mystery.

Trevor Harris' audition, frankly, borders on disaster. He knows his lines--even at his worst, Trevor can still do that--but the feeling isn't there. There's no spark, no passion, no conviction. As he's on the verge of flailing and failing, an older gentleman at the back of the room catches his eye. Old Jewish guy. He smiles benevolently at Trevor

And something clicks in Trevor's mind. Without warning or explanation, he becomes his role. He believes. And it shows.

The producers' and the director's shock at the change is palpable. Where did this come from? Jesus, we were just about to have this jerk escorted off the lot! What the hell?

The audition finishes. Though clearly impressed, the folks in charge of casting want to discuss, and weigh the merits and potential calamities of hiring this notoriously troublesome (and obviously mercurial) actor as the face of their multi-million dollar project. They begin to thank Trevor, and assure him they'll be in touch, when the dark, diminutive man at the center of their table rises and says, That won't be necessary; I've made my decision. Mr. Harris, you're hired.

Sputters of stammering protest erupt around him, but the man who spoke remains firm and unmoved. I'm the director. This is my project, my vision. I have complete authority on all casting, as per my contract. This goddamned movie wouldn't even be considered if not for me. Trevor Harris will be my Jack Mystery. Miles Franklin--comic book writer, comic book artist, comic book sensation, and now first-time movie director--smiles at Trevor, and adds, Congratulations, Mr. Harris. Trevor. May I call you Trevor? I'm Miles. I look forward to working with you.

The assembled gathering of bigwigs shift nervously, but swallow pride and apprehension long enough to rise, gladhand, feign enthusiasm, and check their expensive watches before leaving the audition room as fast as their fat legs can carry them, bound for martinis and mistresses and whatever illicit balms they can apply to their malaise and unease. Miles Franklin lingers only a bit longer than his twitchy colleagues, and he congratulates Trevor one more time before likewise taking his leave. Trevor is alone, and stunned by the sequence of events.

Mr. Harris?

Oh--not quite alone, after all. Trevor looks up as the old Jewish man he'd seen before approaches him, and extends his aged, bony hand in greeting. They shake hands.

You were very good, Mr. Harris. Trevor feels uncharacteristically humble, and smiles at the man. Thanks. Um--thanks very much. Honestly, I don't know what the hell just happened here. Trevor pauses, and looks the man straight in the eye. I mean...I saw you, while I was auditioning, while I was..well, while I was failing. Something about you, man. What...?

The man brushes Trevor's unfinished question aside. Well, I'm happy it worked out for you, anyway. My name's Kirby Simon. My dear, late friend William Hand and I created this character such a long, long time ago. If he were here, William would agree with me. My boy, you are Jack Mystery!

Trevor doesn't reply. But in his head, a voice says, Yes. Yes, I am. He is momentarily dizzy, then suddenly filled with an unfamiliar sense of strength, of purpose. He looks down, and realizes that he has picked up a heavy weight that was left as a prop for the audition. But not really a prop--a real weight, thick and solid and heavy. It twists in his fingers as if it were Silly Putty. Like another superhero before him, he is bending steel in his bare hands.

I AM Jack Mystery!

--

That was my premise for Jack Mystery in the '80s (albeit considerably expanded today, in its first real written treatment, such as it is). If the story continued, we would have seen Trevor believing he was indeed Jack Mystery, but with the actual super powers to prove it. Movie studio execs would be unsure of whether they should intervene, or if they should allow this livin' and breathin' and occasionally crusadin' Jack Mystery to earn free publicity for the new film. Trevor would come to his senses before long, retaining the super powers, and also retaining the sense of responsibility and fair play that he'd felt within himself as Jack Mystery. He would clash frequently with auteur Miles Franklin over the film's dystopian take on superheroes, and he would develop a deep friendship with Kirby Simon. When Simon dies suddenly, Trevor and Miles Franklin would unite in efforts to see Simon's family reap the financial benefits of Jack Mystery's success. An executive from Imperial Media would become a real-life Dr. Skeleton, as well. And Trevor would mend fences with brother Charles back in Buffalo, and even with ex-wife Trish (who would nonetheless marry someone else anyway). He never would remember Marcie's name. Er...Darcey's name. Carrie. Roberta? Damn it...!

|

| Good ol' whatsername. Or maybe it was Trish. |

Well over thirty years later, I look back on Jack Mystery not so much as a missed opportunity, but as a fond memory of the creative process. This is likely all that anyone will ever hear of this superhero I created as a child, a character I returned to play with again as an adult. There are some cherished playthings of youth that never lose their appeal. Here's to you, Jack. Wherever you are.

I've mostly written non-fiction. If you're curious about my attempts at fiction, you can check out the introductory chapters of my (you guessed it!) unfinished rock 'n' roll superhero time travel adventure ETERNITY MAN!, and a completed Batman short story that I think turned out pretty well: The Undersea World Of Mr. Freeze. Reminders that I should stick with writin' about power pop are probably not necessary.

No comments:

Post a Comment